Horror’s Full Gamut: Fear as Shown in The Exorcist

By Trey Sorensen

I believe The Exorcist is the scariest movie of all time. I say that as objectively as possible. The film deserves this honor not necessarily out of qualitative fact, but as a quantitative one–there just seems to be something for everyone to be scared of within the film’s propulsive two hours, depicting a wide range of fears common to the human experience.

There’s the basic stuff like the fear of the dark, played upon as Chris MacNeil investigates noises in her attic, our frame lingering on the empty black spaces for just a little too long.

Then there’s the fear of heights, evoked first as the camera pans the two-story fall of the Georgetown house that ostensibly claimed the life of Chris’ director Burke Dennings. We feel that same tingle in our necks, that same insecurity in our balance, staring down the now iconic step street of stairs–precariously steep and narrow.

But then there are the more cerebral, more cultural and more introspective fears that are explored. Regan’s possession is notably paralleled with her puberty and is in fact, within the film’s story, initially written off as nothing more than wild hormones. She is no longer the little girl that her mother once knew and therefore Chris fears she has lost her daughter, not yet necessarily in terms of life and death but as a matter of connection. Chris fears she no longer knows who her daughter is and what she is capable of.

We are confronted with our fears of embarrassment, displayed as Regan interrupts the wrap party with a show of public urination before an audience consisting of dear mother Chris, her esteemed guests, and ourselves–all of us cringing and turning away in vicarious mortification for poor Chris, whose sustained anxiety (a sort that would be there for any actual, real-world parent) is marked as she relates the story to Father Karras, figuring that his colleague, present for the incident, had already indiscreetly described it. Much to her relief, he had not.

Father Karras’ driving characteristic in the film is his fear that his faith is in vain. He questions his belief in God–only to be convinced of His existence in the worst, most nightmarish way possible.

Karras’ storyline also plays with a fear of failure. He leaves the care of his aged mother to a negligent uncle, who passes the buck again to a run-down sanitarium. Conditions are dire, and guilt stirs inside Karras. Unable to see her before she passes, he is without closure. It is that fear of unforgivability that Pazuzu throws back at the priest, taunting him with mimicked cries of his mother begging for help and putting him into rage.

Many more fears are depicted in The Exorcist, but I’d like to finish with one that is induced in the film–one that is novel, and unique to the movie-going experience. Clipped only a few times through the film are subliminal flashes of Pazuzu’s true face. These fraction of a fraction glimpses of his unsightly, horrifying visage are seared into us, their afterimage lingering even behind shut eyelids. It’s typical for people to want to look away at a horror movie’s scariest parts, but The Exorcist denies its audience that refuge. What makes The Exorcist so incredible is that you will be made too afraid to even close your eyes.

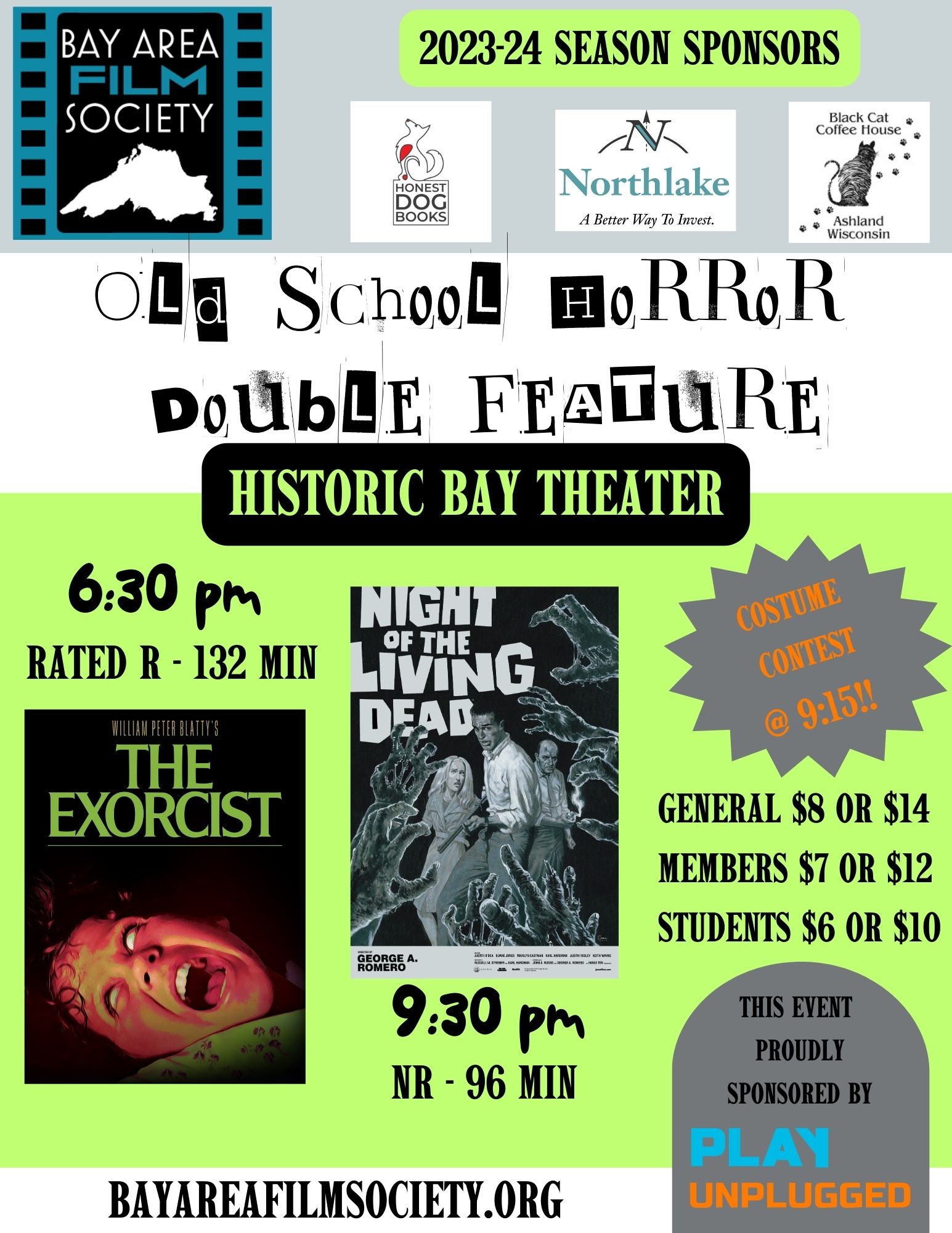

The Bay Area Film Society will be showing a special 50th anniversary screening of The Exorcist at the historic Bay Theater in Ashland, WI on Friday October 20th at 6:30 pm, coupled as a double feature event with Night of the Living Dead. In between the two shows will be a Halloween costume party that you surely will not want to miss. See you at the movies.